Session 1 – Overview & Colonial (1790-1880)

‘Constructing a History of Australian Art,’ Professor Sasha Grishin, AM

Australian art should not be viewed as a reflection or echo of art developing internationally but should instead be recognised as having its own particular voice – this was the premise of Grishin’s presentation.

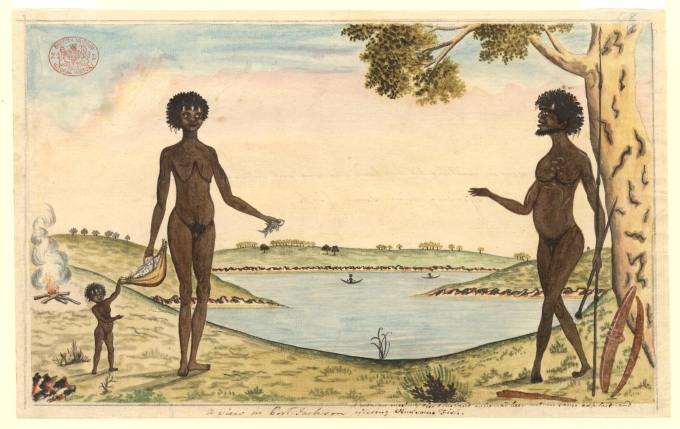

Through highlighting a series of images of Australian Aboriginal* petroglyphs, Grishin argued they formed part of a sophisticated and independent stylistic tradition which had developed for millennia prior to European contact. He proposed that a hybradised art style resulted post-European contact when amateur artists responded to the artistic conventions of Aboriginal art, such as shown in the work of the Port Jackson painter (below). Grishin’s view was thus that Aboriginal art played a role in the development of art on the Australian continent, with the artistic process being influenced in both directions.

A view in Port Jackson. A woman meeting her husband who has been out on some exploit and offering him some fish, Port Jackson Painter, (c. 1788-1797)

A view in Port Jackson. A woman meeting her husband who has been out on some exploit and offering him some fish, Port Jackson Painter, (c. 1788-1797)

Grishin spoke of the post-contact art tradition of painting the corroborree or other Aboriginal cultural scenes ‘from the outside looking in’ such as was done by John Glover in his work A Corroborree of Natives on Mills Plains. Aboriginal artists such as William Barak turned this method on its head. Barak had no need to set the scene, his drawings were from an inside perspective and were a way to preserve the culture of his people for generations.

A corroborree of natives on Mills Plains, John Glover, 1832

A corroborree of natives on Mills Plains, John Glover, 1832

Figures in possum skin cloaks, William Barak, 1898

Grishin stated that Australian art is of this place and not imported from abroad. Ian Fairweather’s work for example, was shown as a synthesis from European, Chinese and Aborignal Australian art, a style which did not sit comfortably in the European or American art traditions. Fairweather’s work was accessible and thus had a profound impact on a wide range of artists over many decades. Similarly, the work of local artist John Brack was concerned with universal issues. He was a painter of Australian reality; he confronted it and engaged with it showing subtle humour and irony. Whilst Brack was aware of international developments in art, his work was not reliant on them.

Grishin turned to the work of Sydney artist John Olsen, whose exhibition The You Beaut Country is currently showing at NGV Australia. Grishin described Olsen’s work as without a fixed identity, but of the Australian aesthetic; a mental explanation of a feeling, the openness of being Australian and the ways of living.

Seafood paella, John Olsen, 2007

In conclusion Grishin argued against the idea that Australian art echoes developments occurring abroad. He argued that Australian art has largely developed independently and encompasses Aboriginal and multicultural influences unique to Australia. Grishin proposed we need to fight for an Australian art identity, which is no easy feat when a globalised world calls for the opposite.

‘Early Colonial Art: Indigenous Representation & Indigenous Response,’ Prof. Brian Martin

The flawed representation of Indigenous Australians and the continued presence of constructed and imagined identities was the premise of Prof Brian Martin’s presentation. Martin argued that the creation of a colonial space and a post-contact national identity resulted in the eradication of aboriginaltiy and declining representation.

Landscapes and portrait studies were used by colonial artists to describe difference, to show the precolonial world as archaic, aiding the settlers view of uncontested possession of Australian land. Martin noted that there is no word for ‘land’ in Aboriginal languages, only ‘country.’ Aboriginal Australians were seen as icons of the precolonial environment and equated with prehistory. Australian art showed the ‘triumph’ of the white settler, an attitude of replace and repopulate, with Aboriginal people replaced by settler culture and the white frontier. Martin argued this revealed a visual discourse of painting Aboriginal people out of existence. He explored the concept of the wilderness, how Aboriginal people were included in wilderness paintings as natural parts of the landscape. Their removal was therefore an act of cleansing rather than dispossession.

The bath of Diana, Van Dieman’s Land, John Glover, 1837

The bath of Diana, Van Dieman’s Land, John Glover, 1837

Over time Aboriginal subjects were Europeanised in continual attempts at erasing Aboriginal identity. However, despite wearing European clothing like everyone else, worn on Aboriginal people it was considered a form of costume dress-up, they were ‘not quite white.’ They were the Other, a novelty; which in turn was equated with savagery. This was somewhat epitomised by the regulation of Aboriginal Australians under the Flora and Fauna Act prior to the 1967 referendum.

Detail from Bungaree, a native of New South Wales, Augustus Earle, c. 1826

According to Martin the inclusion of white settlers in Australian landscape paintings therefore created a desired sense of civility, as shown in William Ford’s At the Hanging Rock. It was a form of Australian nationalism; deleting and replacing Aboriginal people with white ‘natives’ in a nostalgic and new non-Aboriginal future.

At hanging rock, William Ford, 1875

Martin poignantly noted that Aboriginal Australians could ‘hand in’ their cultural heritage in order to better their position in life, literally signing documents which prohibited any expressions of Aboriginality, including language, dance and spirituality.

Martin argued that the collective amnesia towards terra nullius has shaped the concept of nationhood today. Australian heroes often had larrakin identities, a sense of lawlessness and evoked the white frontier, as did Ned Kelly. However when a great sporting hero such as Adam Goodes dared express his Aboriginality in public he was vilified, highlighting deep seated fears from white Australia. In an increasingly globalised world the cultural search for authenticity will continue.

Floor talks – notes

Rebecca Edwards, Assistant Curator Australian Painting and Sculpture

John Glover

- Glover depicted the landscape for what it was. He captured the particular lighting and vegetation specific to the landscape.

- The Indigenous population had been wiped out from the area he lived in.

- Glover provided a European view of the colonial settler community.

- He preferred brooding and dramatic views compared to the traditional pastoral scenes of his contemporaries.

Eugene Von Guerard

- Von Guerard’s work was a celebration of settlement.

- He first went to the Ballarat Goldfields to strike it rich before moving to Melbourne.

- His focus was on geologically and botanically significant sites and remote wilderness areas and his work was ordered, smooth and contained.

- He had scientific eye and an acute sense of direct observation.

- The colouring in his work is drawn from his experiences of being in the landscape.

*Aboriginal and Indigenous Australian terminology was used interchangeably by the speakers. I chose to use the same language they used.

One thought on “NGV’s Illuminating Australian Art Course”