Introduction – Catherine Leahy, Senior Curator, Prints & Drawings at National Gallery of Victoria

The 1880s saw increased activity by Australian artists, with those born or trained in Australia coming to the fore. Tom Roberts introduced artist colonies and Arthur Streeton’s artist camp became famous. The 9 by 5 Impressionist Exhibition was also a product of this era. Led by Tom Roberts, Charles Condor, Arthur Streeton and Fred McCubbin, the exhibition showcased the sketch-like qualities associated with Impressionism painted on nine by five inch cigar box lids collected from tobacconists or on boards, canvas and sculptured panels.

In 1888 on the centenary of white settlement in Australia, artists and writers responded to the nationalist sentiment. During this period Tom Roberts produced the famous Shearing the Rams (1890), Fred McCubbin painted his iconic The Pioneer (1904) and Hans Heysen introduced the gumtree as the new symbol of Australia.

Fred McCubbin, The Pioneer (1904)

Fred McCubbin, The Pioneer (1904)

Australian artists were not isolated from overseas. Australia attracted a cosmopolitan art scene, with European visitors and Australian art students travelling to Europe and particularly to Paris to study. Expatriates were highly regarded.

The aboriginal artist William Barak was also active during this period, producing a body of art and a record of his culture whose people are largely absent from paintings and their welfare largely ignored.

Australian Impressionism – Jane Clarke, Senior Research Curator, MONA

A newspaper article in the 1880s claimed that ‘Australian can only be painted by impressionists.’ However following the 9 by 5 exhibition, the artists in a letter to the Argus stated ‘we will not be led by compositions of light and shade.’ This became the manifesto for later Australian impressionism.

Tom Roberts, The Artists’ Camp (1886)

Tom Roberts, The Artists’ Camp (1886)

Tom Robert’s The Artists’ Camp (1886) resulted from the artist camps where they discarded the studio in favour of painting in situ in the open. They sought to make informal compositions or snapshots, no doubt influenced by the rise in photography. The capacity to paint conveniently outdoors also coincided with the development of paint tubes in the 1850s.

Instead of the high finish, impressionists sought to remove the hand of the artist, a concept that was well known to those attending the Heidelberg School. Sydney Dickinson asked the question in a newspaper article ‘What should the artist paint?’ He believed nationalist images, life around you and local figures in local environments was the answer. In Europe the tendency was to sweeten and sentimentalise the urban poor and ‘clean them up.’ This happened less in Australia as there was a sense of power and energy in paintings of Australian people. The artists felt at home in the landscape and had the ultimate knowledge of their environment.

Australian impressionist art suggested nostalgic and heroic landscapes. The Brothers of the Bush for example were active in Melbourne, artists societies were cropping up and the camaraderie from painting in outdoor camps was increasing. Australian artists retained stronger structural form in their depictions of figures compared to their French contemporaries for example. They used a more constrained palette and their art was more serious and sufficiently finished. According to Clarke this was not impressionism in the sense Europeans knew it. It was common for Australian impressionists to use sturdy figures in the foreground but keep the background in the traditional impressionist style. They were able to paint in different manners for different purposes.

The Australian landscape was well suited to optimistic moods and wide tonality. White under-painting was used rather than the previously taught dark tones. Gold and blue was the colour scheme used in Australia, as exemplified by Arthur Streeton’s The purple noon’s transparent might (1896) which, although unlikely, he claimed to have painted on the spot. Streeton depicted a great sense of light, warmth, air and atmosphere. The use of hazy pinks with blue and the gold light of Australia were lauded by Clarke.

Arthur Streeton, The purple noon’s transparent might (1896)

Arthur Streeton, The purple noon’s transparent might (1896)

Critics thought impressionism was raw material and not something for sale. The artists knew they were part of a trend and critics would eventually like the works in spite of themselves. This was exemplified by the 9 by 5 exhibition in which works were sold and whatever was left was auctioned off. Streeton called this a turning point for Australian art. Attendees were able to listen to music and drink cups of tea in a Japanese themed gallery complete with parasols. It appealed to fashionable people, the press and art critics alike.

By the end of the century Australian impressionism was well established. Whilst there was an exodus during the 1890s, most returned. Roberts declared; ‘Australia hasn’t fairly been touched yet!’ by artists.

Australian Expatriate Artists – Dr Anna Gray

The numbers of Australian artists who went overseas and stayed away until the end of WWI was quite extensive. Many experienced hard times and lived in squalid conditions. Interestingly, Hugh Ramsey had a meagre income but hired a piano to host musical evenings. Australian artists preferred Paris and spaces where students taught themselves and were visited by established artists once or twice a week for critiques.

It was common for those on scholarships to send their works back home. Many made copies of great works by Velasquez and the like and began creating their own interpretations of the works. George W. Lambert was known for modelling himself of Velasquez and painting new compositions of the original. He reprised many early art pieces and turned them into his own versions, a practice that became common amongst Australian artists and internationally. Gray stated it was a post-modern act before post-modernism itself. Lambert looked to Italian artists such as Bronzino, Botticelli and to Manet. This was highlighted by comparing Lambert’s The Sonnet (1907) with Manet’s Luncheon on the grass (1862) and Titian’s Le Concert Champetre (1509).

George W. Lambert, The sonnet (1907)

George W. Lambert, The sonnet (1907)

Edouard Manet, Luncheon on the grass (1862)

Edouard Manet, Luncheon on the grass (1862)

This reworking of earlier art was also a trait of Roberts, who influenced by the long portraits of Whistler, created Blue Eyes and Brown (1887) which drew on the Japanese influences in Whistler’s work to capture the softness of the young girl.

Another artist John Russell had worked with Monet and was influenced by his style. He succeeded in the old Salon and Royal Academy and wanted to show his work to more modern societies. He started to paint the same scenes at different times of day, in different lighting and weather conditions.

Australian artists also started moving towards the Edwardian depiction of nudes in the outdoors and women wearing looser clothing. It was controversial at the time, with the argument that looser clothing equaled healthier women and thus children, was floated frequently.

Other changes were the use of new decorations, creation of works on silk or undertaking commissions to decorate houses, as did Charles Condor. The use of colour also changed through the influence of the Ballets Russes, with bright bold colours in and the creation of artificial power through dance as was seen in Madame Melba (1902) by Rupert Bunny.

Lambert and others became official War Artists or took on other roles during WWI. Gray described Hilda Rix Nicholas as painting from her soul, he family had died as result of illness and then her husband was killed action; the effects of war was something she knew too well. Lambert would go on to work on major compositions in the last years of his life that focussed on his war experiences.

Lambert, A sergeant of the light horse 1920

Frederick McCubbin’s The North Wind c. 1888 – Michael Varcoe-Cokes, Head of Conservation, National Gallery of Victoria

The North Wind appeared to be a man standing in front of a horse drawn cart carrying his wife, child and their wordly belongings in a windy and barren landscape. The painting was of a time when the idea of a ‘finished painting’ was up for debate. Some saw it as a transitional work for McCubbin, striking a balance between the contained academic depiction of the horse and the expansive background.

The painting had been on display until ten years ago when the NGV removed it for conservation assessment. Under UV light, previous heavy-handed attempts at restoration appeared as did a tear and evidence that the painting had been previously folded. Extensive reworking had occurred prior to 1941 in ways that would not be acceptable today.

X-ray analysis also highlighted the small tear and provided information on the order of how paint was placed on the canvas; i.e. the horse was painted first then the sky. The X-ray also indicated a second horse behind the cart had been painted over, as had some of the landscape. Another horse head in a higher position at the front of the cart also appeared. Evidence of the canvas stretcher bar and cracking was visible, with its off-centre placement indicating the painting was originally wider. Light beam analysis at the Australian Synchrotron also provided elaborate data mapping of the use of individual pigments across the painting, enabling NGV to deduce his son repainted the signature during restoration; thus explaining why the signature date was out by two years.

These examinations highlighted that McCubbin developed and reworked the piece over time and that it suffered over time through various restoration attempts. By NGV removing old restorations and other motifs, the colours became much more vivid, the blue more intense and the sky as expansive as McCubbin would have intended.

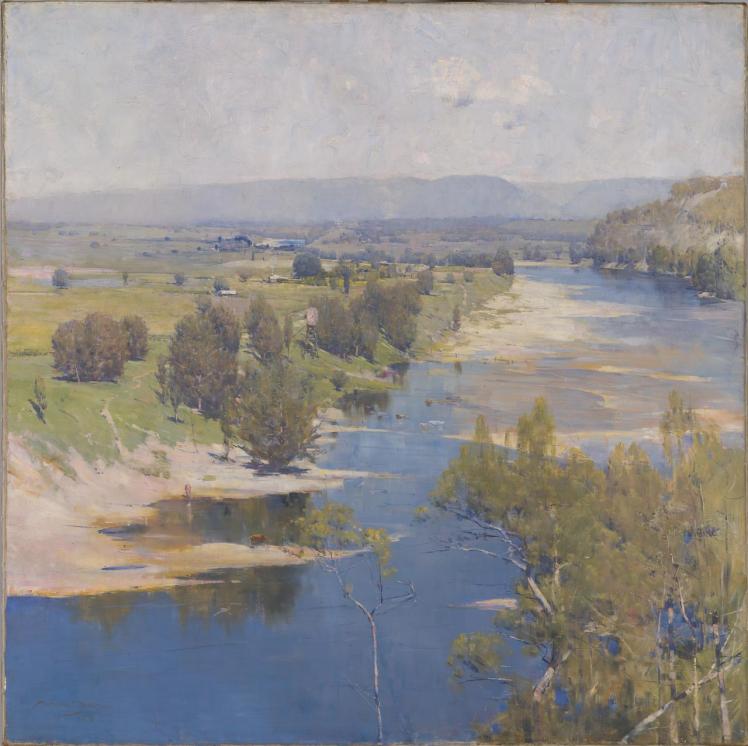

Arthur Streeton The Vale of Mittagong (1892) – Catherine Leahy

Whilst he was not well known in his early career for his watercolour work, The Vale of Mittagong was a major piece in the career of Arthur Streeton. The watercolour medium was portable and easy to use, if a difficult medium to become proficient at. Australian watercolours were known for their crisp and brilliant light of the Australian milieu and the rich colour of the landscape.

In 1891 Streeton embarked on larger and more ambitious watercolours as a result of his participation in a NSW watercolour competition where 12 prizes worth up to 75 pounds each were up for grabs. He worked in the Blue Mountains near Penrith where he painted Fires On, but did not win and returned to Melbourne. In 1892 he went back to Sydney and began painting in Mittagong. An enthusiastic letter writer, Streeton wrote to Roberts from the Commercial Hotel; ‘I have spent four to five days on a picture in Gibraltar Rock, 400 feet up. Done my best.’ In another letter to his friend Professor Hall he spoke of a ‘1 ¾ mile walk to Gibraltar Rock’ which he would scale slowly and lay out his ‘traps for a days work. North, South, East, West you can see for miles. I was so fatigued from my climb there was little left for my picture. I climbed for five days.’ He goes on to wax lyrical about the ‘atmosphere and the waves of ranges – truly Australia.

Streeton began The Vale of Mittagong with compositional outlines and broad colour washes. Over the top he then worked with other colours and the wooden end of the paintbrush to scratch back in highlights such as smoke and tree trunks. Artists used an array of techniques for working back into the medium whilst it was still wet.

The Vale of Mittagong is an extraordinary panorama. Streeton captured the vast scale of the landscape but also a wealth of detail, i.e. the waratah blooming on Gibraltar rock (NSW logo), the train, roads and farm buildings. The horizon line is also high in the image, departing from landscape conventions adhered to by Rembrandt for example. Streeton was known for his introduction of this composition, with its breadth and sense of grandeur. ‘Even the atmosphere seems thin and sparse,’ Streeton said. Leahy observes that the crisp detail and the notion of seeing through to the distance really comes across. There is a glorious; truly Australian and poetic feel to this painting. As Streeton was known to quote romantic poetics like Shelley, this seems quite fitting. Streeton captured the hidden poetry of the Australian landscape that he knew was there and wanted to convey.